An architect’s job is to create spaces that meet the needs and accommodate the welfare of the people using them. This project proposes how a community can be made in collective housing, not just within the walls of the building but also in collaboration with the local community.

“Third places” are spaces outside the home and work where you can interact with your neighbors, creating a local community. Modern-day apartments have all these luxury-dubbed amenities that function as third places. However, the downside is that these facilities are available only to apartment residents, cutting out all outsiders and thus gentrifying the community.

The question that is brought up is, “How can we make the space of connection something that can be experienced, not just in an individual home but in a collective dwelling?” This project’s answer is to create a flowing circulation that creates opportunities to develop a community for both residents and residents nearby.

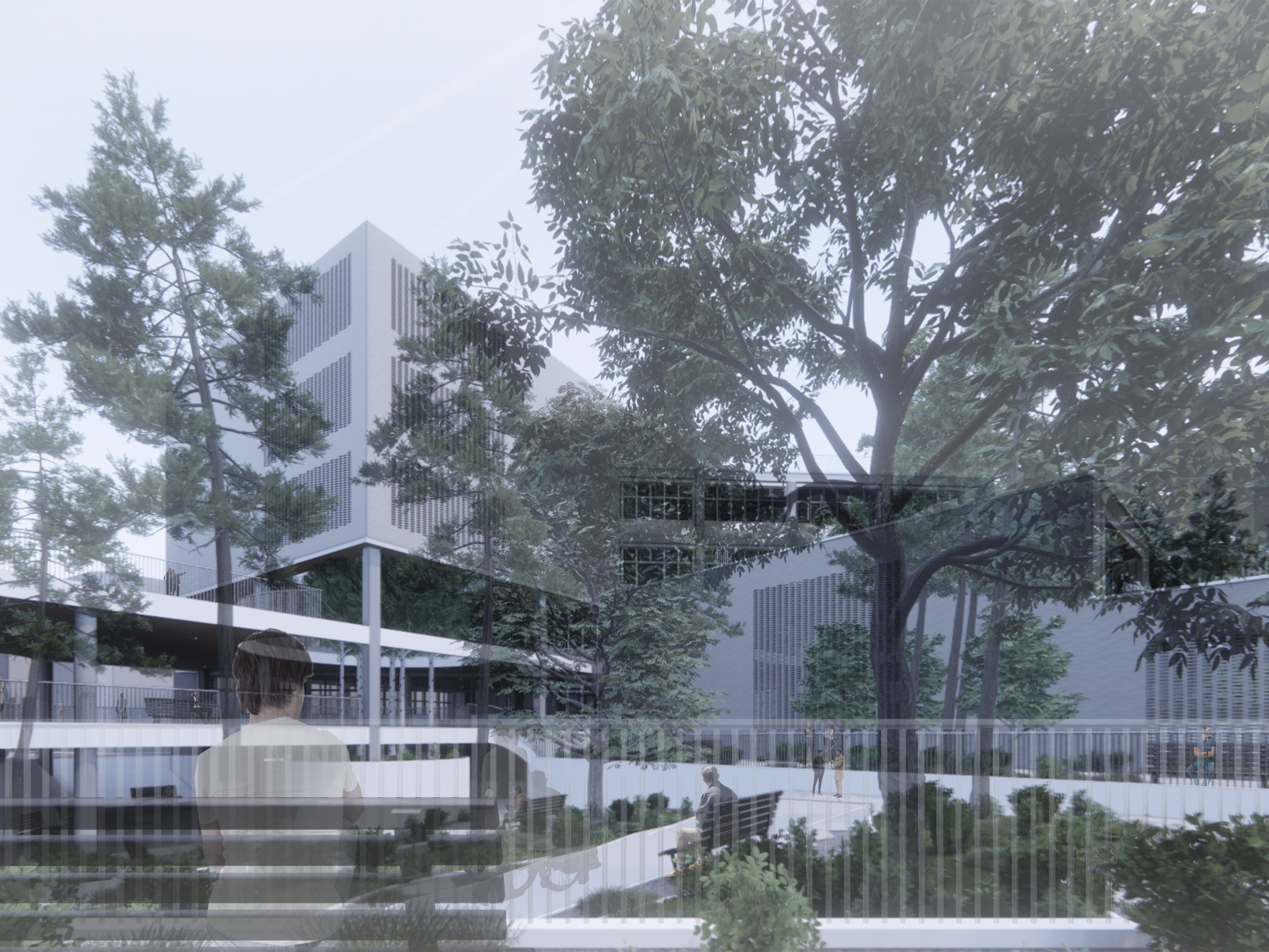

The third place of this project is the entire ground floor. The building mass separates the ground floors and creates various spaces that vary in elevation, shape, and size. These areas are full of surprises, just like the people that bump into each other there. Residents of the building, pedestrians that are walking on Broad Street, and people that are visiting the shops that face Peachtree Street all commingle in this “carpet”, creating a third place that includes all.

Now, what about community between the residents? When you live in a multi-unit housing complex, there are some instances where community can be fostered, such as pressing the elevator button for your neighbor, seeing others in the building’s courtyard, and saying hi in the hallway. How can these moments be architecturally translated to a building that incorporates a “carpet” scheme for the ground floor?

The scheme is extended to the upper floors by creating an interior courtyard that visually connects all the floors down to the ground. The units form several clusters, and each cluster has a courtyard where you can see all the other neighbors and pedestrians. Each cluster has its vertical core, so neighbors bump into each other when they ride the elevator. Finally, the unit’s balconies vary in orientation and shape, which sets the stage for a community’s “balcony dance”.

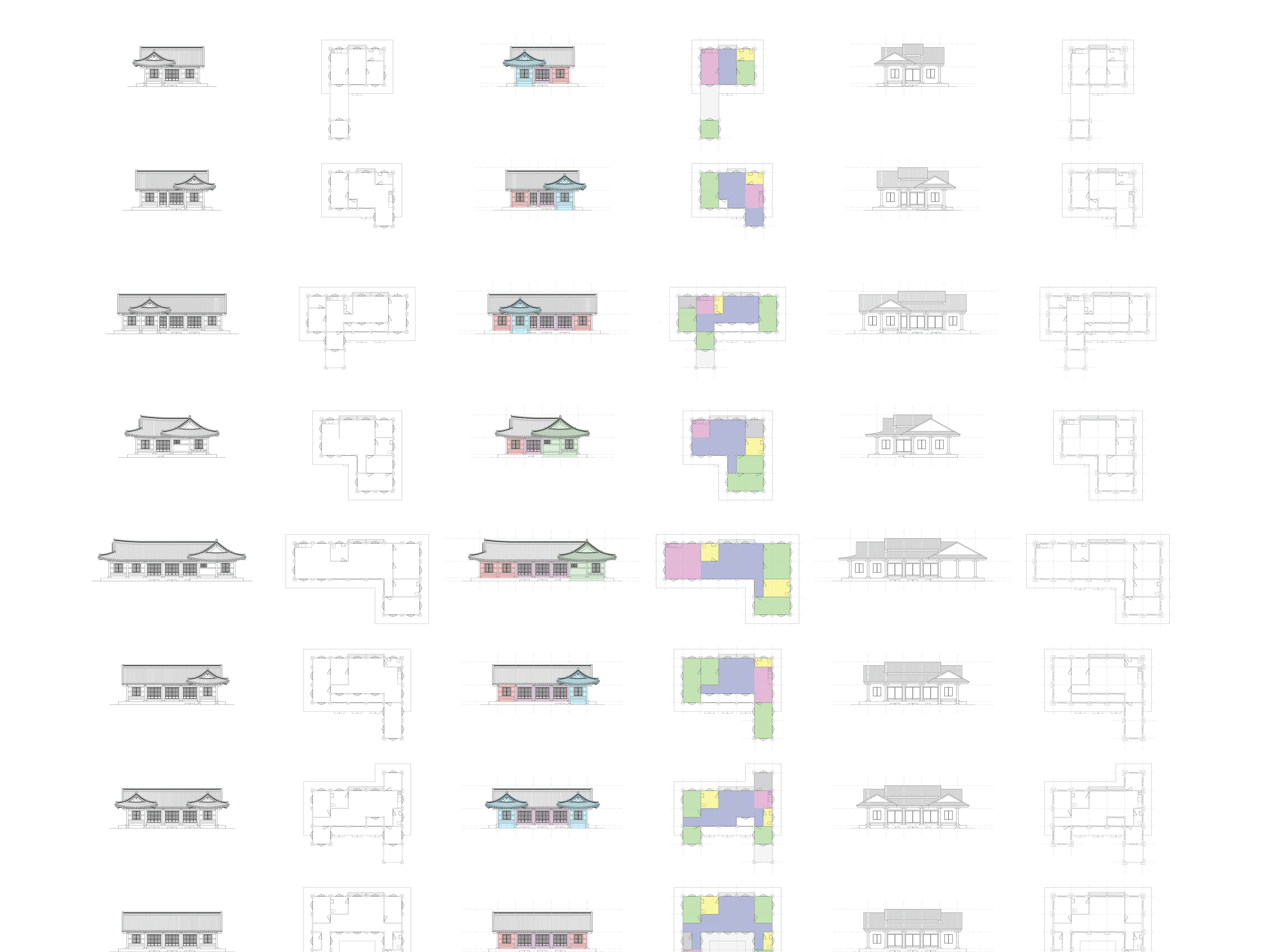

Now, to the environmental issues. The mass of the project is dictated by how the housing units are placed. This specific orientation is to resolve the conditions that the physical environment of the site provides. Two sides of the large site face buildings, which complicates sunlight and ventilation issues from the units that are far from the site boundaries.

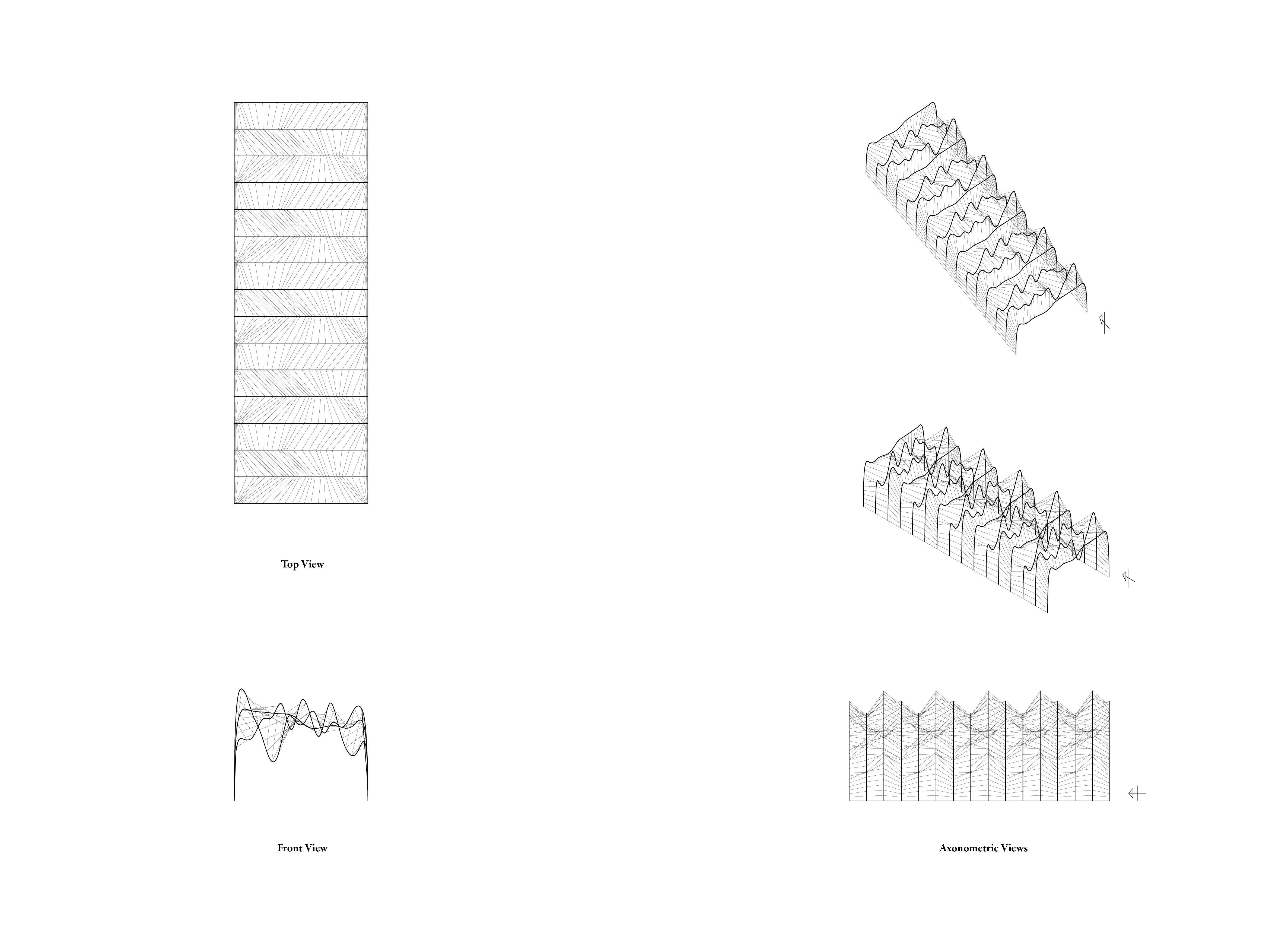

Of all the unit requirements, the notable ones that directly impact the entire building orientation are 1. they must occupy at least two orientations per unit, 2. all rooms must be naturally ventilated, and 3. no corridors within the unit. These requirements further strengthen the courtyard concept.

Environmental sustainability-wise, housing regulations have become stricter. To meet the environmental standards of modern-day buildings, natural cross-ventilation has been adopted in the project to employ less mechanical cooling. The long “slow space” that directly connects both sides of the unit functions not only as a means of fostering community but is also utilized to accelerate cross-ventilation. This scheme is expanded to the entire unit, where the courtyard acts as a vent that sends the hot air up.